How might we help people in small residential communities be more social?

THE CHALLENGE

Getting to know people is hard, especially when you’re new to a city or away from most of your friends and family. Meeting people online is easy enough, but how are people supposed to form in-person relationships in the digital age? Our challenge was to understand what it means to “know your neighbor” and explore opportunities to facilitate socialization in small residential communities.

MY ROLE

I lead the the interaction design, UI design, and industrial design. My team mates and I all contributed to the generative research, research analysis and synthesis, concept development, and user testing.

Duration

8 weeks (Feb 2015 - Apr 2015)

Research and problem statement

My team was presented with a single, broad constraint of determining, “What does it mean to know your neighbor?” We came up with a plan to talk to anyone we could and ask them very simply, “What does it mean for you to know your neighbor?” Because this was the first user research-focused project for most of my teammates, we wanted to make sure that it would be fairly easy for us to get access to a large group of users. So, we introduced another constraint, and limited our interview subjects to city-dwellers.

DIVIDE AND CONQUER

We then split off, and conducted some very short interviews. Then, we reconvened, listened to the recordings, and tried to see if we could identify and similarities. We were able to come away with three key concerns that our interviewees had with regard to knowing their neighbors:

Have my back: Most of the people we talked to were interested in getting to know people who live near you without the burden of constant interaction. Several interviewees talked to us about how they feel safer and more secure when they have people looking out for them. That said, some people expressed concern about being obligated to spend too much time with their neighbors.

Show me what's going on: Other people that we interviewed expressed an interest in discovering events and special deals that were going on around them. A handful of the people we talked to expressed a desire to access this kind of information not only when then they were at home, but also at work, since this is somewhere they also spent a lot of their time time.

Keep my friends and neighbors separate: Lots of people we talked also shared that they like to plan events (like BBQs) for meeting and getting to know neighbors. But, they also stated that they didn't always want to have to call to invite a neighbor to an event or have to add them as friends on Facebook. They liked having the freedom to only interact with their neighbors within the vicinity of their complex or home.

INFO GATHERING

Most of the interview subjects that we selected were between the ages of 18-30. Because this project was moving pretty fast, and we wanted to make sure we would have a decent pool of people to pull from for further research and testing, we figured that it would make sense to design a solution for young professionals and college students.

The next step for us was to write and distribute a survey to respondents that met our research criteria (lives in a city, between the ages of 18-26), with the goal of understanding some of their decision making strategies around event planning.

We learned that, on average, our 86 respondents consider themselves to be technologically savvy. This could suggest that there is some opportunity to push the envelope regarding new technologies and/or innovative applications of technologies.

Side note: We acknowledge that, because this information is self-reported and pretty subjective, it is possible that the respondents' perceptions of their technical literacy is inaccurate.

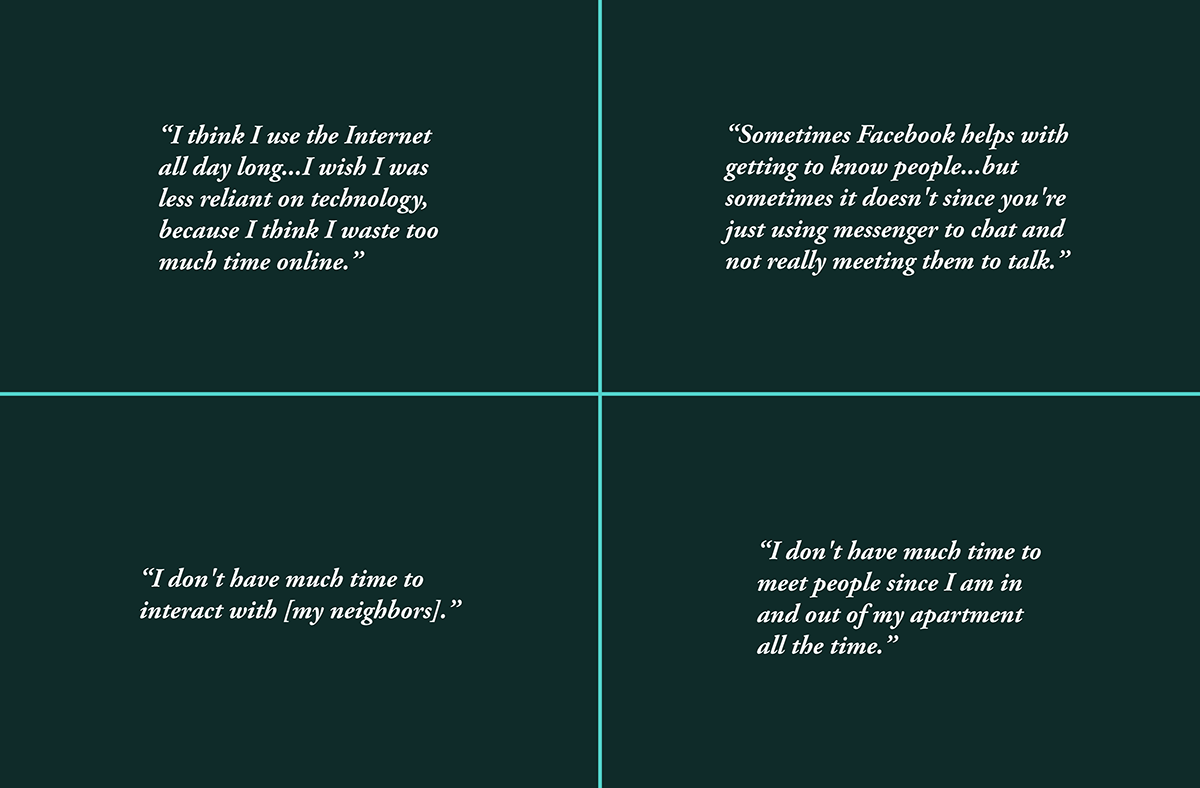

Perhaps the most interesting thing our data revealed was that most participants do not know their neighbors as well as they would like. We identified this as an area that we would like to know more about, and set up some in-person interviews. I pulled some quotes from the interviews that particularly stood out:

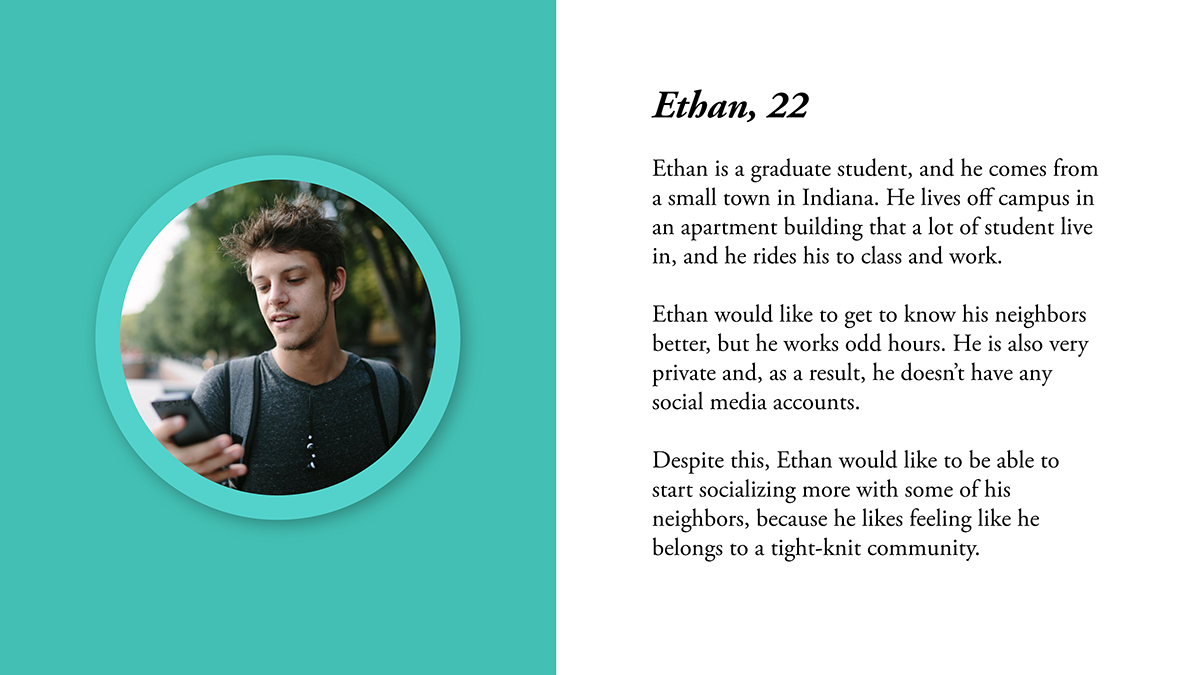

As we were talking to and surveying our users, some patterns amongst our users began to emerge. I took this opportunity to craft some simple personas to serve as inspiration as we prepared to move into concept development.

Solution exploration

When we asked interviewees about how they hear about neighborhood events that are interesting to them, two outlets kept coming up: Facebook and flyers.

This ranged from seeing posts that people might make about events happening around the neighborhood to Facebook event pages which allow users to send each other invitations and have a common place to discuss the event.

The problem with using Facebook, though, is that it carries a certain level of intimacy that not every neighbor might wish to share.

Flyers, on the other hand, are either posted in a common place or mailed to residents of the neighborhood. We found that people tend to be receptive to flyers because they are typically created by a local neighborhood organization, which lends a certain amount of legitimacy to whatever events the flyer promotes. The main issue with flyers, though, is they only provide a one-way means of communication. Inquiring further about whatever the flyer advertises requires the recipient to engage in secondary method of communication with the person or organization that commissioned the flyer.

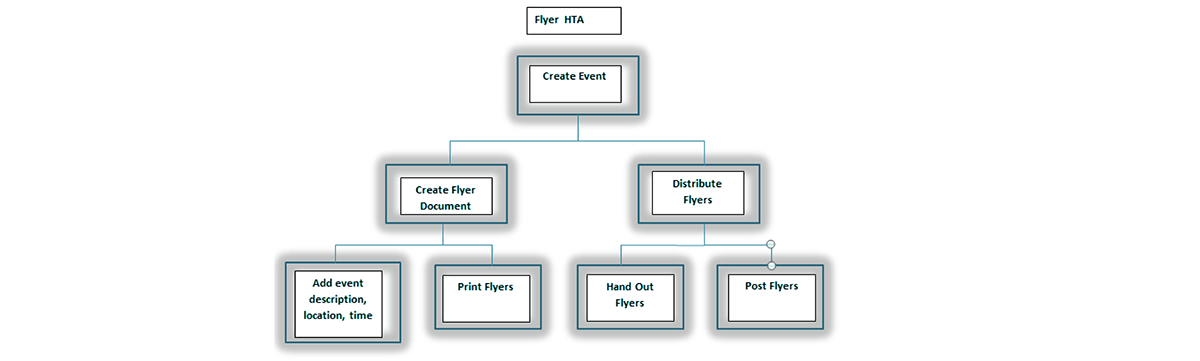

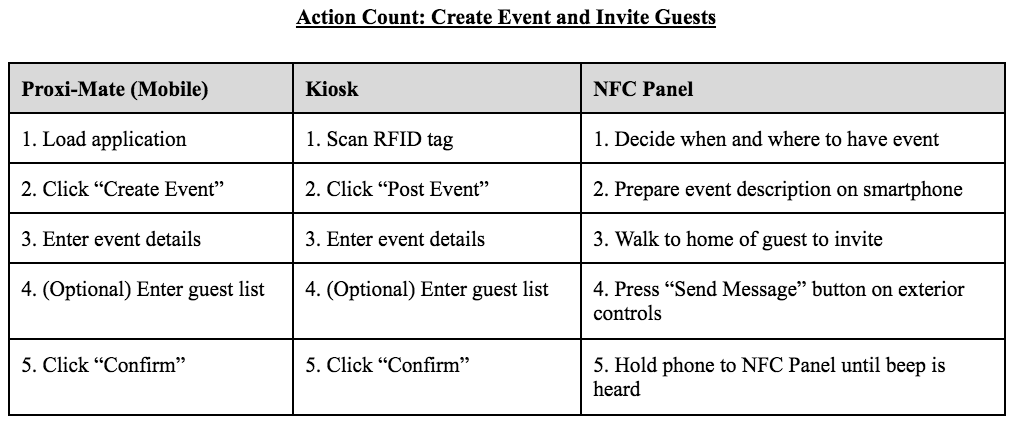

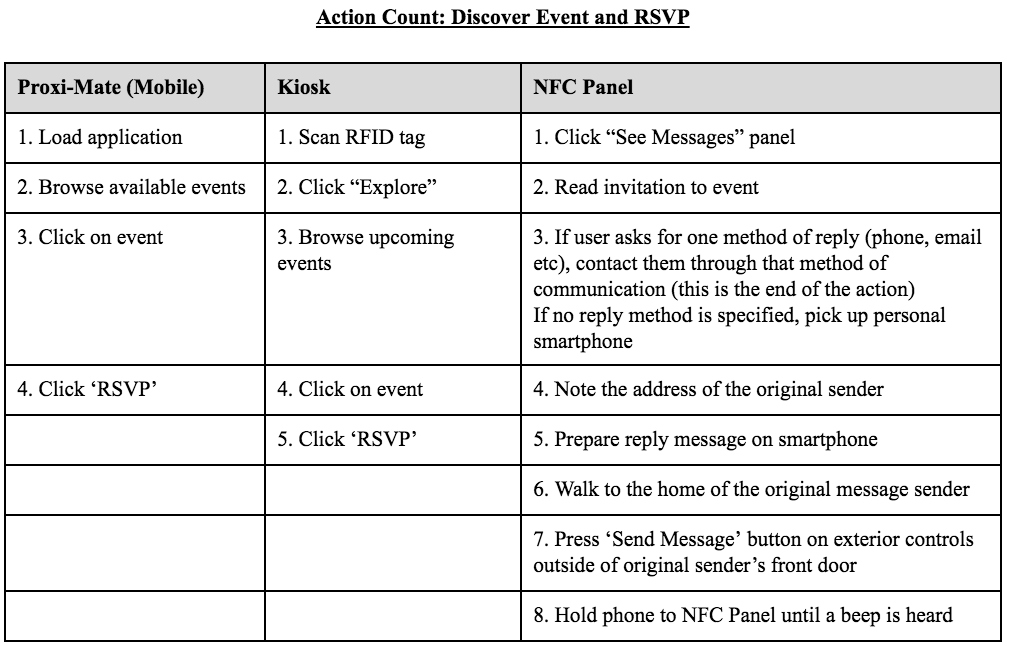

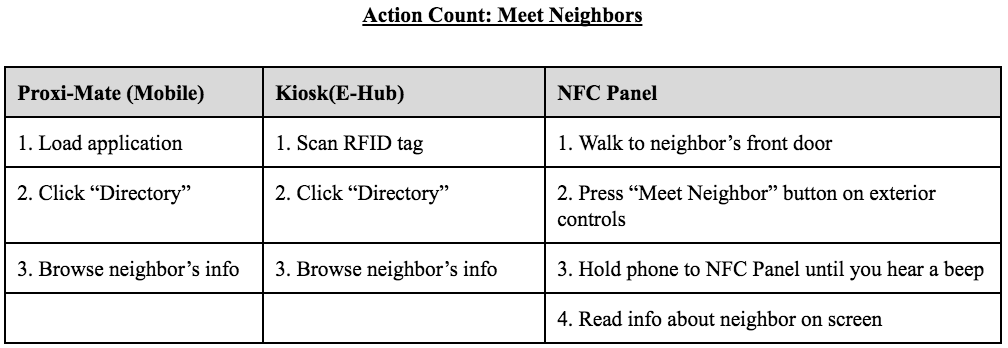

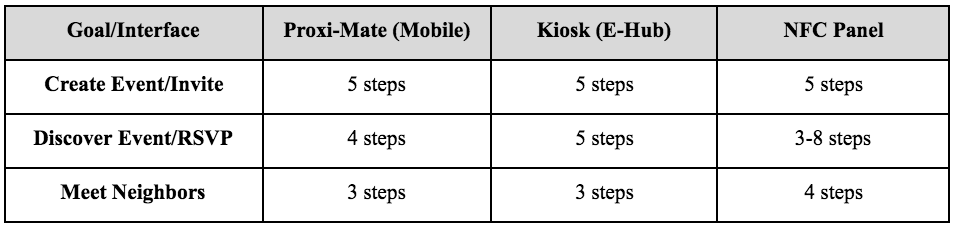

To get a better understanding of the tasks associated with each these existing methods of communication that users need to perform to achieve certain goals, we considered the common task of creating an event and performed as hierarchical task analysis.

Facebook HTA

Flyer HTA

Based on some of the language we heard in our interviews, we were able to come away with a system metaphor, an interactive neighborhood bulletin board, to help inform our design decisions and help us plan for different features.

In order to meet our users where they are, while still striving for an innovative solution, we developed some key actions and requirements that our solution would need to support:

Advertise event: For users who create an event that is open for anyone in their neighborhood to attend, the system should allow the user to advertise or send messages about their event effectively.

Discover events: Neighbors should be able to easily discover upcoming events in their neighborhood.

Basic communication: Users that create an event should be able to communicate with any number of their guests. Likewise, guests should be able to contact the event coordinator if they have any questions or concerns.

Security/privacy: Only basic information about the neighbors should be available in the system. Additionally, details about events that are closed invitation should only be seen by those who are invited. Neighbors using the device should only be able to login as themselves.

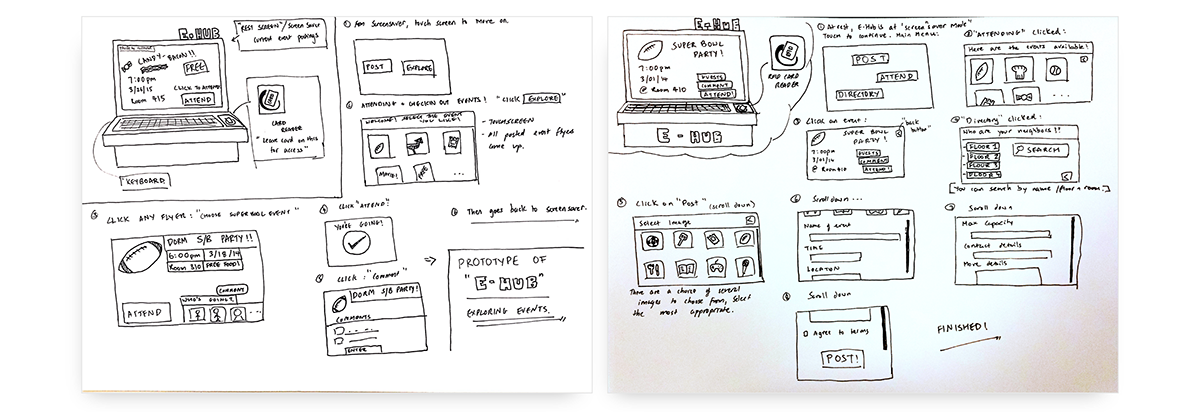

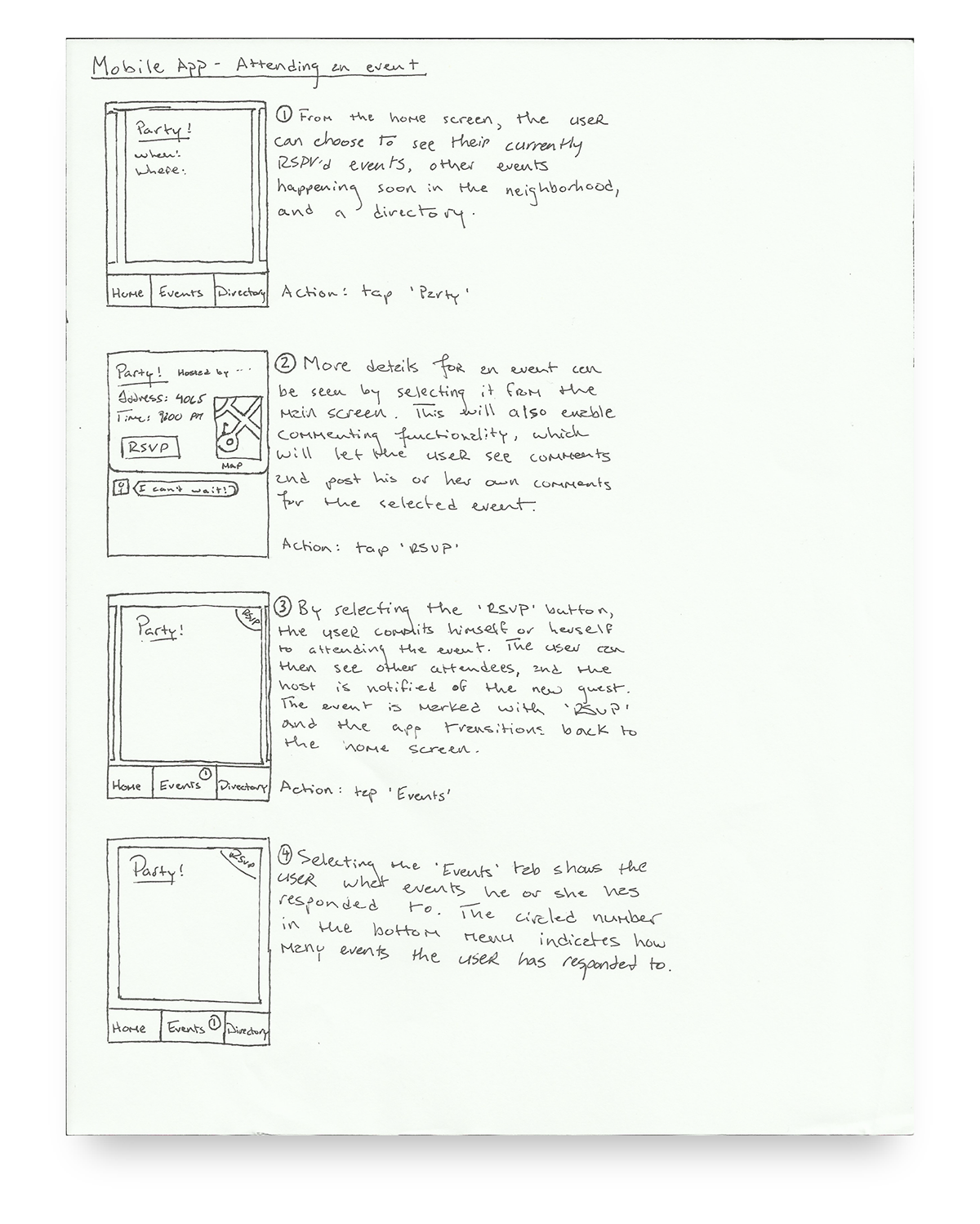

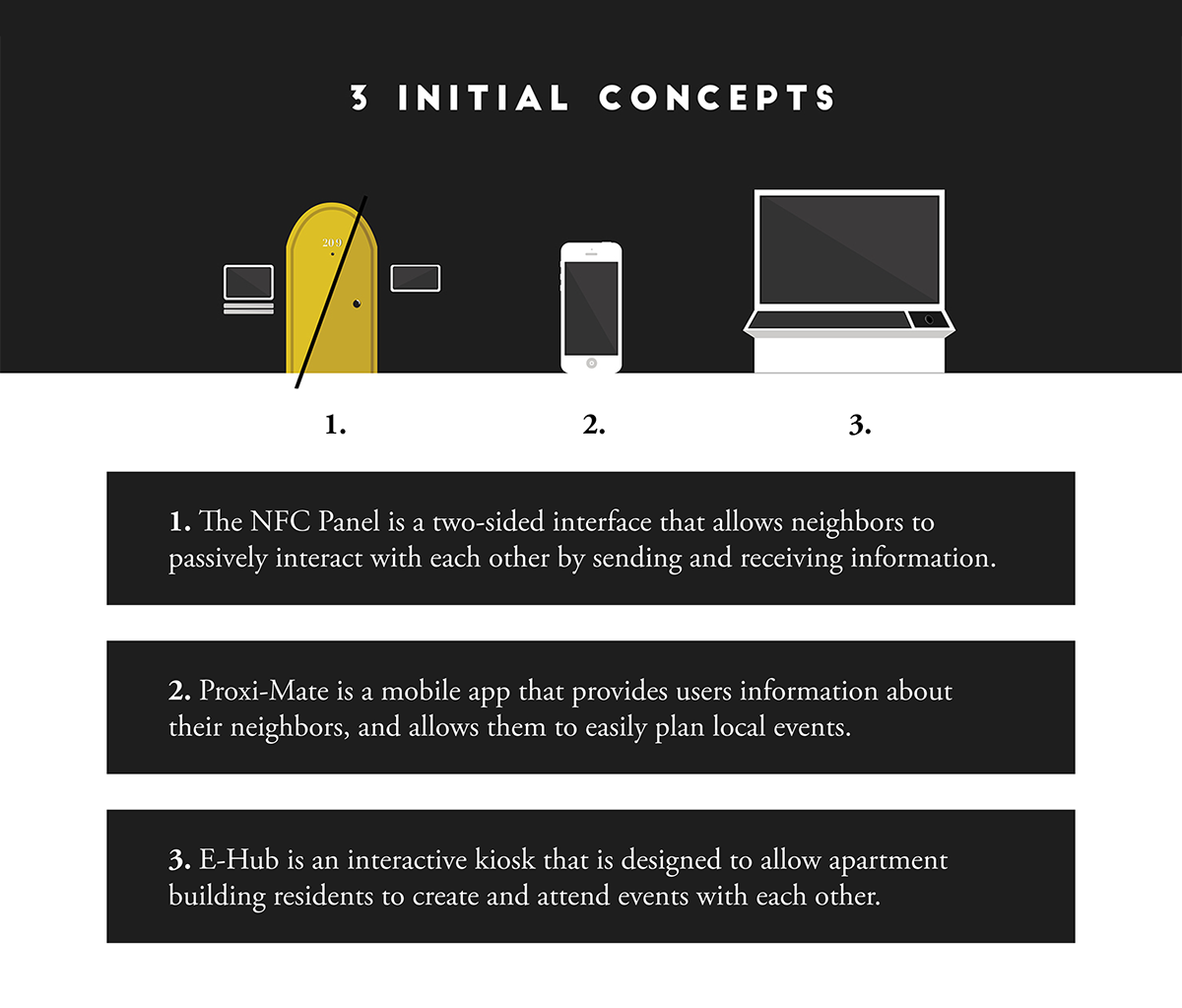

GENERATING ROUGH CONCEPTS

With our metaphor and functional requirements in mind, we began sketching. For the sake of time, we narrowed our ideas down to our top 3 concepts and focused on those.

Sketches by John Koh (www.johnkoh.design)

Sketches by Richard Hernandez

Sketch by Gabrielle Bales

With an eye towards innovation, we forced ourselves to write concept descriptions, that we would later critique alongside the sketches, in order to solidify our ideas.

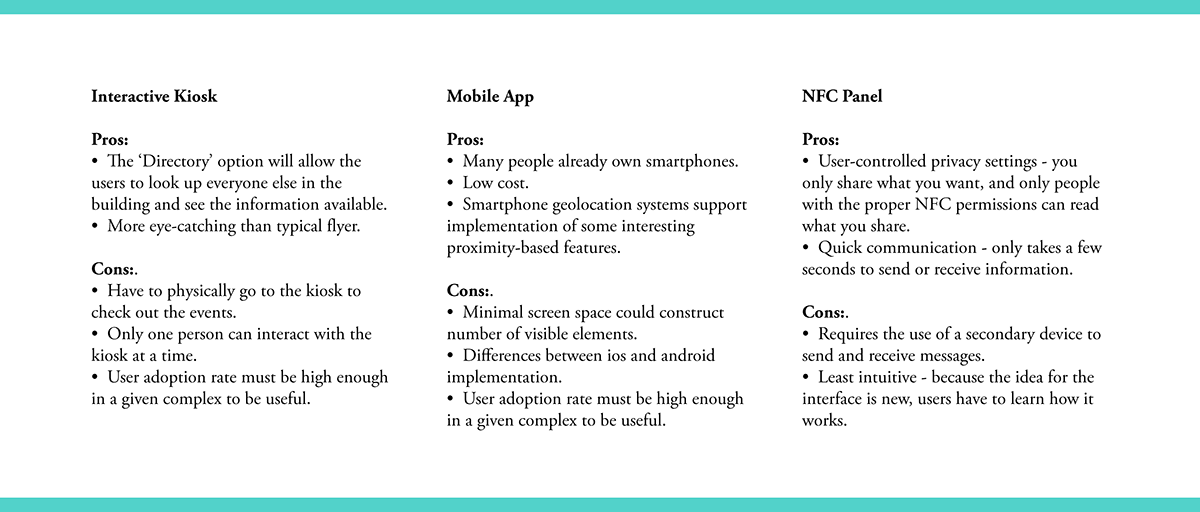

As a group, we studied the designs and made our own list of pros and cons for each concept.

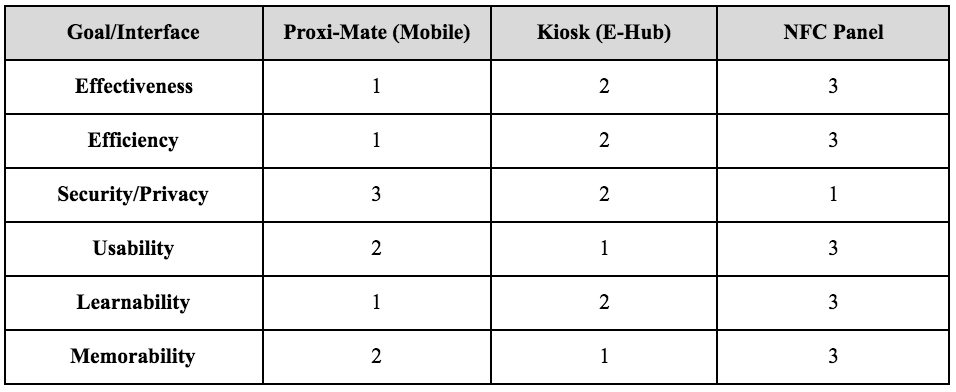

To help narrow our focus, we made some assumptions about some high-level steps that would be involved in the execution of the primary tasks. We then ranked each concept based on how it measured up against some predetermined usability criteria.

After reviewing the results, we were able to come up with a hybrid solution that we hoped would include the best elements of each idea. In order to help explain this concept to others, we again relied on the use of metaphor and started describing it as a digital door bell and mailbox.

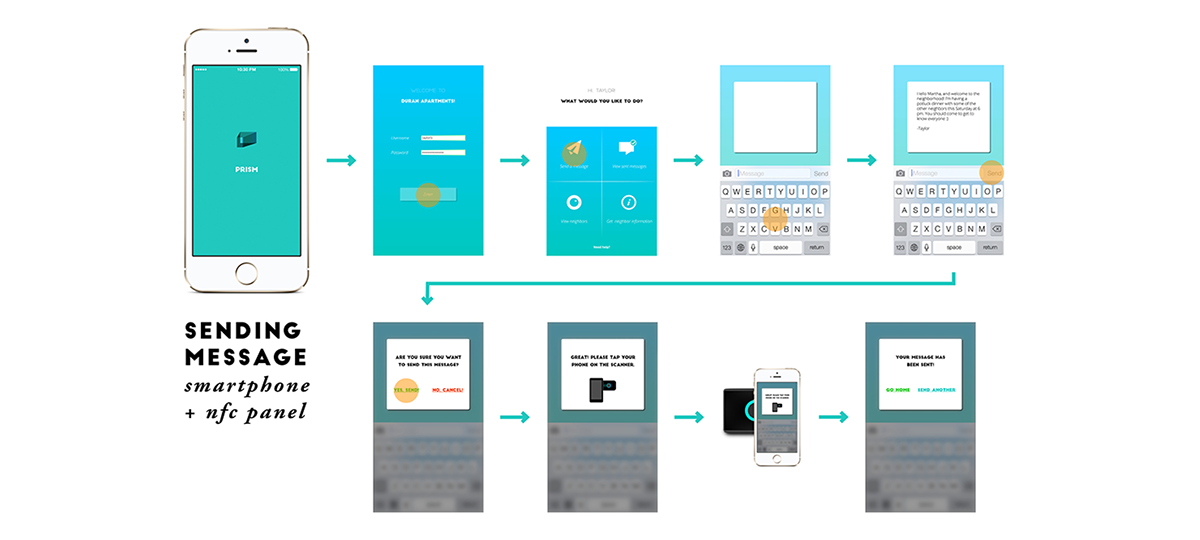

The NFC (near-field communication) panel coupled with the mobile app allows neighbors to engage in passive communication with one another.

Evaluation and testing

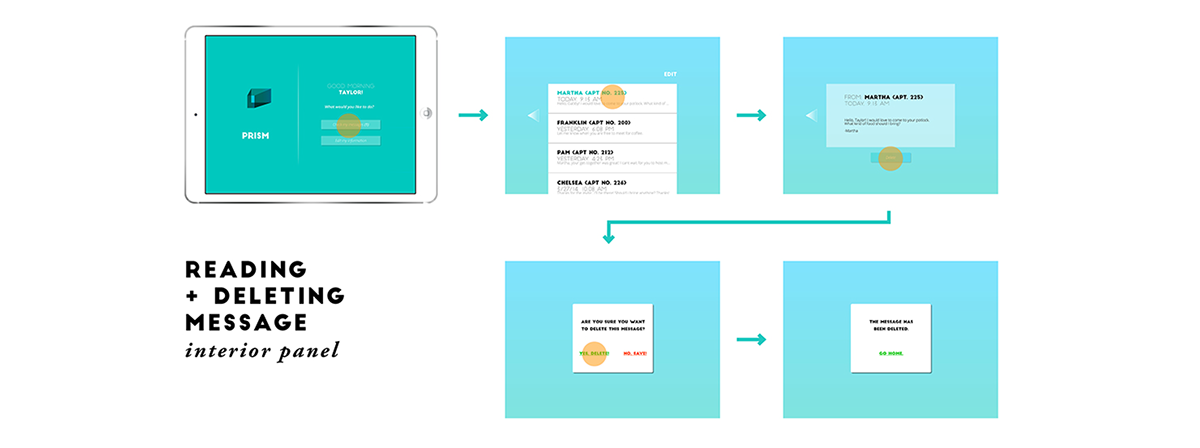

We were able to test our prototype with participants in settings that would ideally be similar to the final implementation. The study consisted of 3 tasks with one being repeated to test learnability. As a team, we selected tasks that represented the primary use cases:

Task 1: Retrieve neighbor information with phone.

Task 2: Send a message to neighbor with phone. (Repeated as Task 4)

Task 3: Access messages on tablet.

Task 4: Send a message to neighbor with phone.

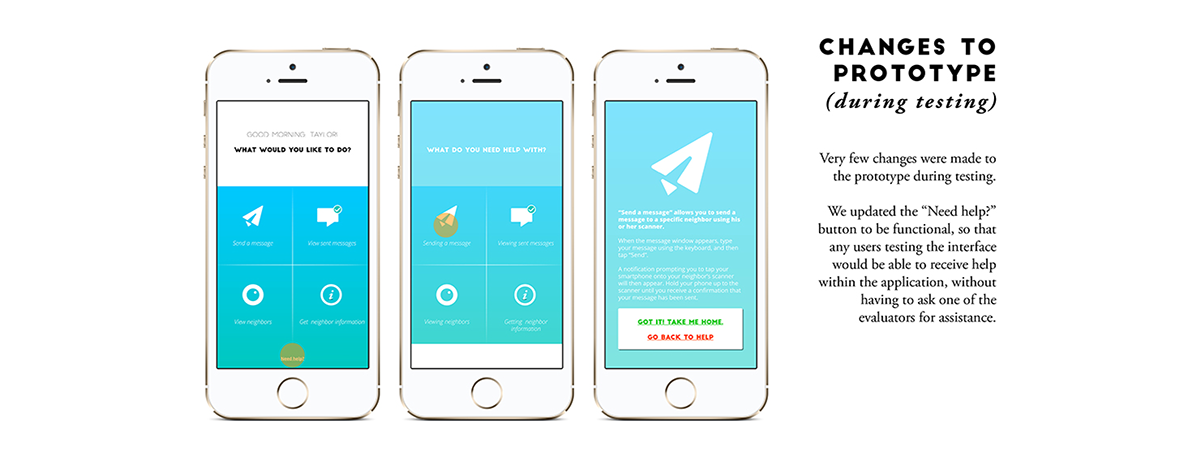

Before testing Prism with users, we ran a pilot test amongst ourselves to ensure we didn’t have any hiccups during the formal testing, as well as to come up with some benchmarks for each task. After running the pilot test, we made note of some issues, corrected those issues, and and moved on to the testing with users.

The study was carried out in a setup created at a university dorm room entrance in order to give the participants a realistic representation of how Prism might actually look. All 10 participants were either college students or young professionals between the ages of 20-26.

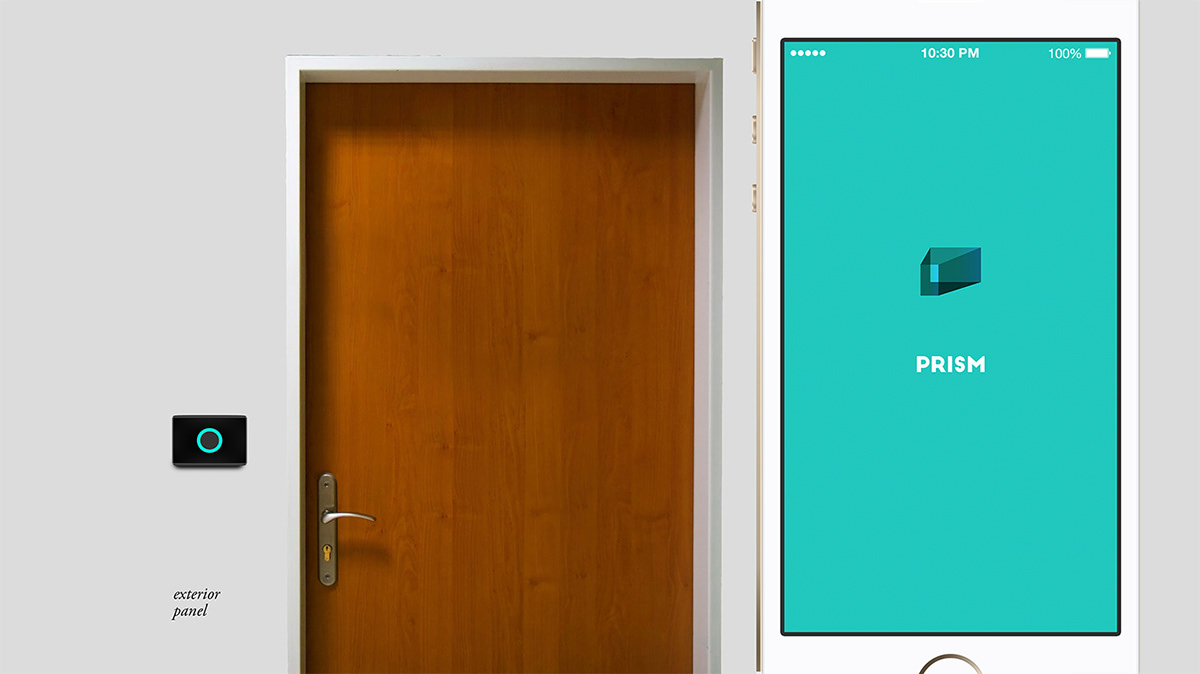

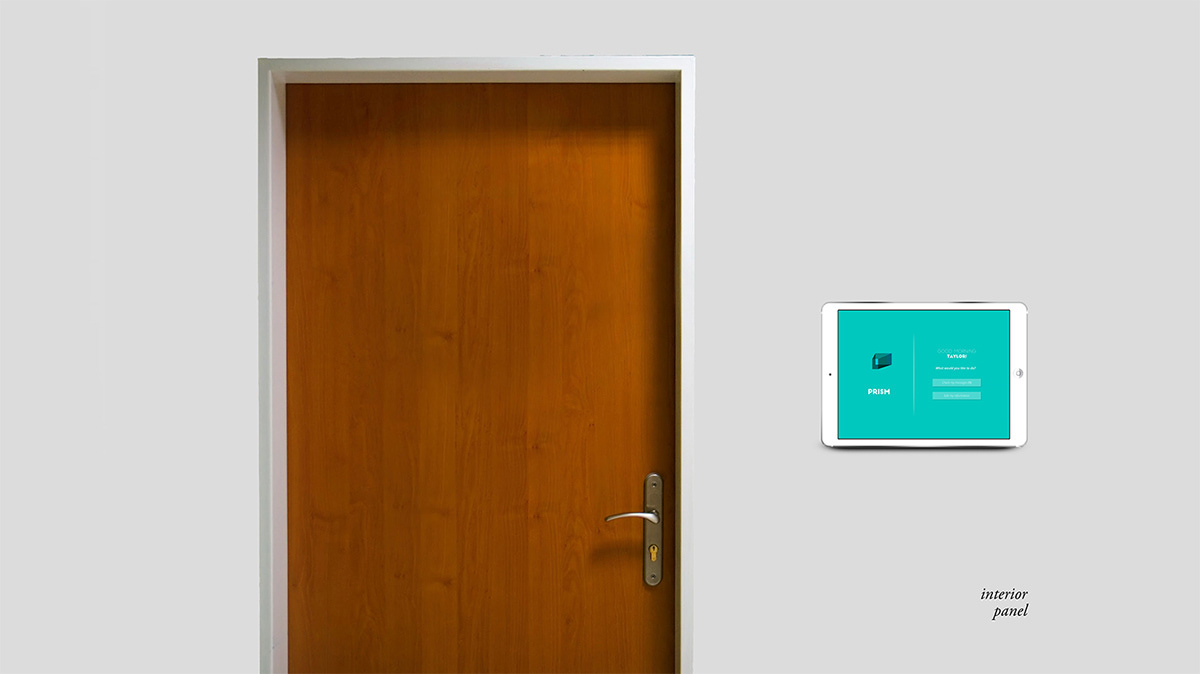

The NFC panel is mounted next to the door in the hallway. Each building occupant would have access to the private Prism app, which would allow each occupant to communicate with every NFC panel.

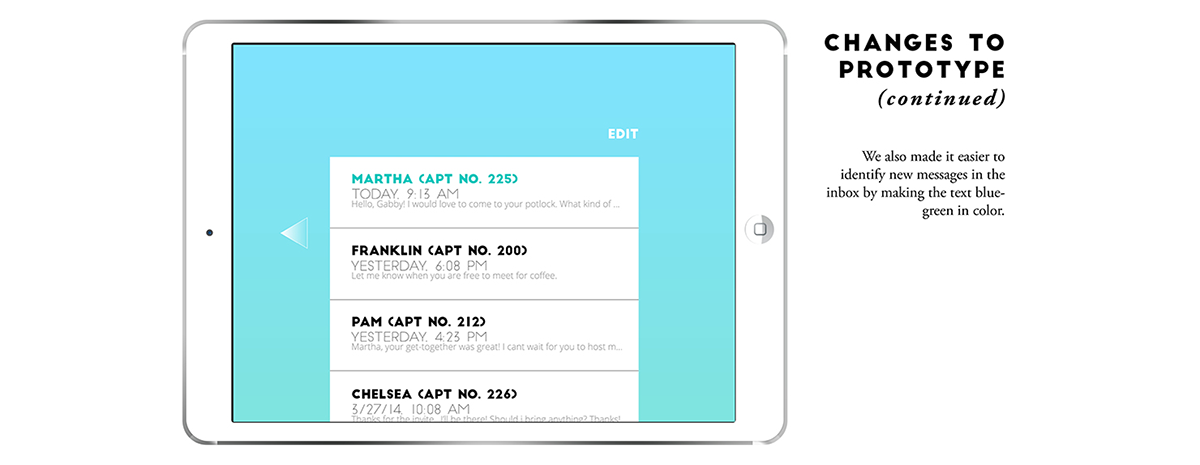

On the inside of the apartment/dorm, the tablet is mounted next to the door. This allows the occupants to read any messages from neighbors, as well as update information that they would like to share with their neighbors.

How it works (InVision prototype): Neighbor A can send a message via the app by hovering their phone over the panel that belongs to a Neighbor B. Neighbor B will then be able to access the message from the tablet inside the apartment or dorm.

RESULTS AND FEEDBACK

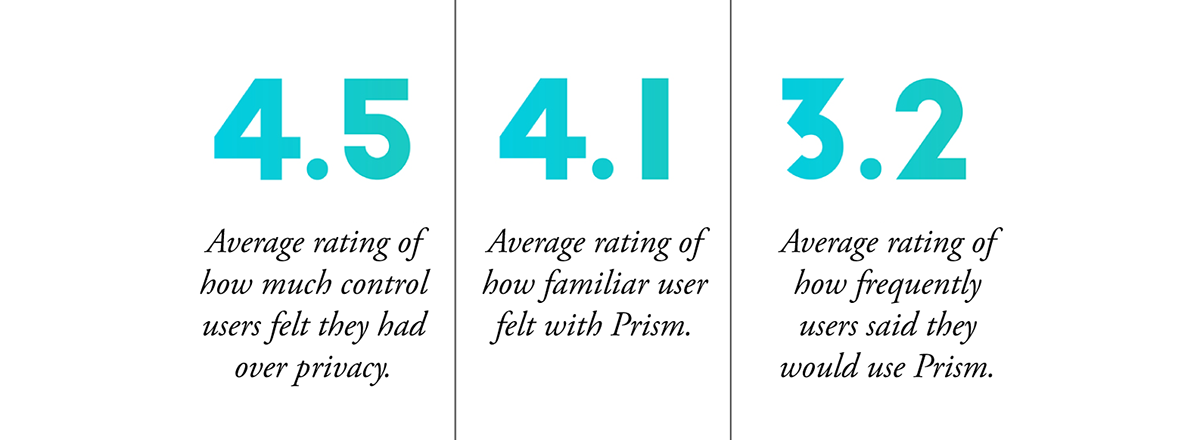

Most participants never asked for any assistance, and were able to complete the tasks without much friction. Those who did ask for help usually just needed help with getting started, but they quickly caught on.

During testing, we monitored the number of times each user tapped their phone screen as they performed each task, and compared those values to the minimum number of taps each task required.

We initially feared that because this system was an entirely new concept, unlike any existing set of tools, that users would not be open to the idea of using it in their day to day life. Our overall assessment showed, however, that users would enjoy using the system.

In our post-session questionnaire, we asked our users to rate how frequently they would predict using Prism. Their responses were recorded anonymously, as we wanted to remove as much bias as possible and get honest feedback. Although our users revealed to us that they didn’t predict that they would Prism as often as they currently use other tools, like their mobile phones, we were excited to learn that many users were open to the idea of using Prism as an alternative form of communication.

Most of our users (7 out of the 10) commented on the simplicity and ease with which they were able to use the system. We learned that our system’s greatest weakness was that a user might not need it once they had already gotten to know their neighbors. This suggests that in an round of iterations, it might make sense to focus on features that would support existing relationships with neighbors, rather than just facilitating meeting neighbors. Another opportunity would be to focus on marketing Prism as a solution for college freshman dorms, where new students live every semester.

It would also make sense to combine functions that serve similar purposes. For example, the screens for sending and receiving messages are entirely separate entities in our current model. It would make sense to try combining both functionalities into a messaging feature.

Takeaways

My team and I got off to a strong start with this project by giving ourselves an interesting problem to solve and some reasonable constraints. Things got hectic around spring break, but our foundation was strong and our findings were guiding us, so we were able to get back on track fairly quickly.

Our concept challenged some of the existing paradigms about how to send messages or communicate with others. What started off as a vague problem statement evolved into an innovative solution to a complex problem. To our great surprise, once we were able to identify a couple of metaphors that resonated with users, we learned that most of them looked at the system with a sense of intrigue instead of confusion. There are a few noticeable holes in our solution, namely the issue of how a person would use this system more than a few times once they were comfortable with their neighbors. Moving forward, it would be interesting to not only see how this system could be adapted to encourage continued use, but also figure out ways of measuring how Prism has or has not facilitated relationship building.