I spent the last several weeks drawing and talking to people at The Bridge, a day shelter for homeless people in downtown St. Louis. This illustrated magazine feature, which I also wrote, is the product of that experience.

This is the article I wrote that accompanies the images above:

Around the corner from the glossy, vermillion front doors of Centenary Methodist Church is a humbler entrance to the same building. A faded maroon awning notes a different address number, 1610, but there is nothing else indicating what this place could be. Nonetheless, pockets of people crowd in and around the parking lot, some rowdy and arguing, some just out to smoke a cigarette. The organization beyond the awning is officially called The Bridge, though on the streets, it seems to be more known for the location than for the name. Ask someone who is homeless in St. Louis whether they have heard of The Bridge, and they might draw a blank. But when I asked Keith, a homeless man who spends most days near Washington University in St. Louis, whether he had ever been inside the Centenary, the name became familiar. “Oh, I’ve been to the church a few times,” he recalled.

In a network of organizations that provide services to impoverished, disabled, and homeless people in St. Louis, The Bridge is the only day shelter. Located in the heart of downtown, like most of the organizations on the St. Louis continuum of care, the mission at The Bridge is to eradicate homelessness through a Housing First program, which prioritizes securing shelter for homeless people, then follows them to help them overcome whatever made them homeless in the first place. Funding is tight, however—as it is with every social work project in this country—and with just one social worker with a few interns, the organization needs the capacity to expand to meet this goal.

I get waved through when I walk under the awning to enter the building. The blue shirts, or security bouncers, are big, friendly guys who are supposed to wand everyone down before they enter 1610 Olive Street, searching pockets and bags for any illegal weapons and substances. But my clothes are ironed, and I’m holding only a sketchbook and a pencil. It feels almost embarrassing to be exempt from screening: it’s just another indicator of the disparity between my privilege as a student at an elite university simply visiting this place, and that of the people who frequent this facility daily.

Walking in, the immediate importance of The Bridge on the continuum of care is much more apparent than is its overarching Housing First mission. Homeless people know about The Bridge because it serves two meals daily and three meals Monday through Thursday, and it offers hours of shelter every day of the week. Unsurprisingly, it is most crowded at meal times and on days with a harsh forecast. Unlike some other organizations on the continuum with stricter criteria for their clients’ mental health profiles, the only rule for entering The Bridge is sobriety. Based on this fact alone, the mission at The Bridge is nobly ambitious because it doesn’t falter at the wider, sometimes less-stable client base it faces.

At the end of the dingy hallway is a volunteer, Peter, who is busy bustling back and forth between a hall marked Peter’s Pantry and a desk littered with envelopes. “Mondays are always crazy,” he says, shaking his head. “About eleven hundred people mark this place as their primary address. And then I have to sort it, like this.” Peter works this desk four days a week, distributing items like Pampers and bath soap from the pantry to guests and sorting mail. For perspective on the number he mentioned, St. Louis is home to an estimated 1,300 homeless people. The census is not certain since homelessness can last weeks or years, and some people go in and out of periods of income steady enough to pay rent. This year, however, on April 1st, 2015, The Bridge began to implement a system to get a better count on how many unique guests use their services. Every homeless guest will have an ID to scan upon entry, which will provide the organization data on their daily needs in the kitchen and pantry, and will hopefully offer some leverage when they apply for grants to fund their food, pantry, and social work programs.

After meeting Peter, I step into the main hangout of The Bridge: the dining room. The atmosphere is empty compared to the parking lot, and I feel like I have wandered into a waiting room. Guests don’t interact as loudly, and there is a tangible feeling of isolation. It’s ironic of me to feel out of place, I realize, since these people would feel stigmatized in many of the places I walk into on a daily basis. I look for a place to sit down with my sketchbook that would be the least intrusive: not right next to someone, but also not shyly in the corner, where I wouldn’t have the opportunity to casually strike up a conversation. But people are seated at every other chair, many sleeping, hunched in their plastic chairs or burrowed into their arms over the tables, or else congregated in tight groups. I am frozen, struck by the strangeness of the idea of having a mission in this room where nothing is happening and everyone who is still awake is studying me.

“Ma’am, could you take my tray? Could you clear this, please?" A middle-aged man a few feet away relieves me of my isolation. I take his tray, glad to use it as an excuse to begin a conversation with someone else. I ask a man at the back of the room where to discard it.

“In those buckets. The tray goes in that one, the other stuff in the other bucket.”

Daniel is settled alone at a table, accompanied only by a Big Gulp from 7-Eleven and two rolls of various papers secured with rubber bands. He looks like he might be in his fifties, and though the whites of his eyes are cloudy, they are kind.

“You know, I’m here on some kind of…weird business,” I begin awkwardly. Daniel’s handshake is friendly. “I’m just trying to get to know some people while I make drawings of this place.” It’s honest, and that’s all I have walking into this room: faith in my social skills and my sketchbook to carve a point of entry. With Daniel, it works, and he launches into his life story, otherwise unprompted.

Daniel hasn’t had a home in years, although how many is anyone’s guess. “I moved back here from Milwaukee in 2008 I think, so I’ve been in St. Louis for three years? Four years? What is it now, 2011? 2012?”

He tells me how he grew up with three siblings in south St. Louis, one of whom was killed, and another who ended up in trouble in Chicago. He never quite finished high school because he just couldn’t pass algebra. He wanted so badly to become an architect, he says, looking at my sketchbook.

“I could have been an artist of sorts, too.” He fixates on this misstep in his education for several minutes, his eyes clouding as he recedes into himself. He is talking as if I weren’t there, and the story blurs. “I think I have this thing called Einstein’s Block, you know, where I’m really good at everything except for one, important thing.” he says.

We make eye contact for the first time in minutes, and he tries to laugh. “My life has just been a long series of almosts.”

He is bashful when I ask if I can draw his portrait while we talk, but he agrees to it after he smokes a cigarette. “I hang out in the park quite a bit,” he continues. “And I’m here in the mornings and evenings, so you can come find me here then. But during the day, you know, I’ve got appointments with doctors and lawyers and things, places to go. So I’m only here the beginning and the end of the day.” I don’t point out that it’s two o’clock in the afternoon.

When I say goodbye to Daniel for the day, I promise to talk again whenever I come around. He removes a rubber band from one of his rolls of papers and takes out a bright green piece of paper.

“Sophia, right?” he confirms, and he writes my name in all caps with his pencil. “Good talking to you.”

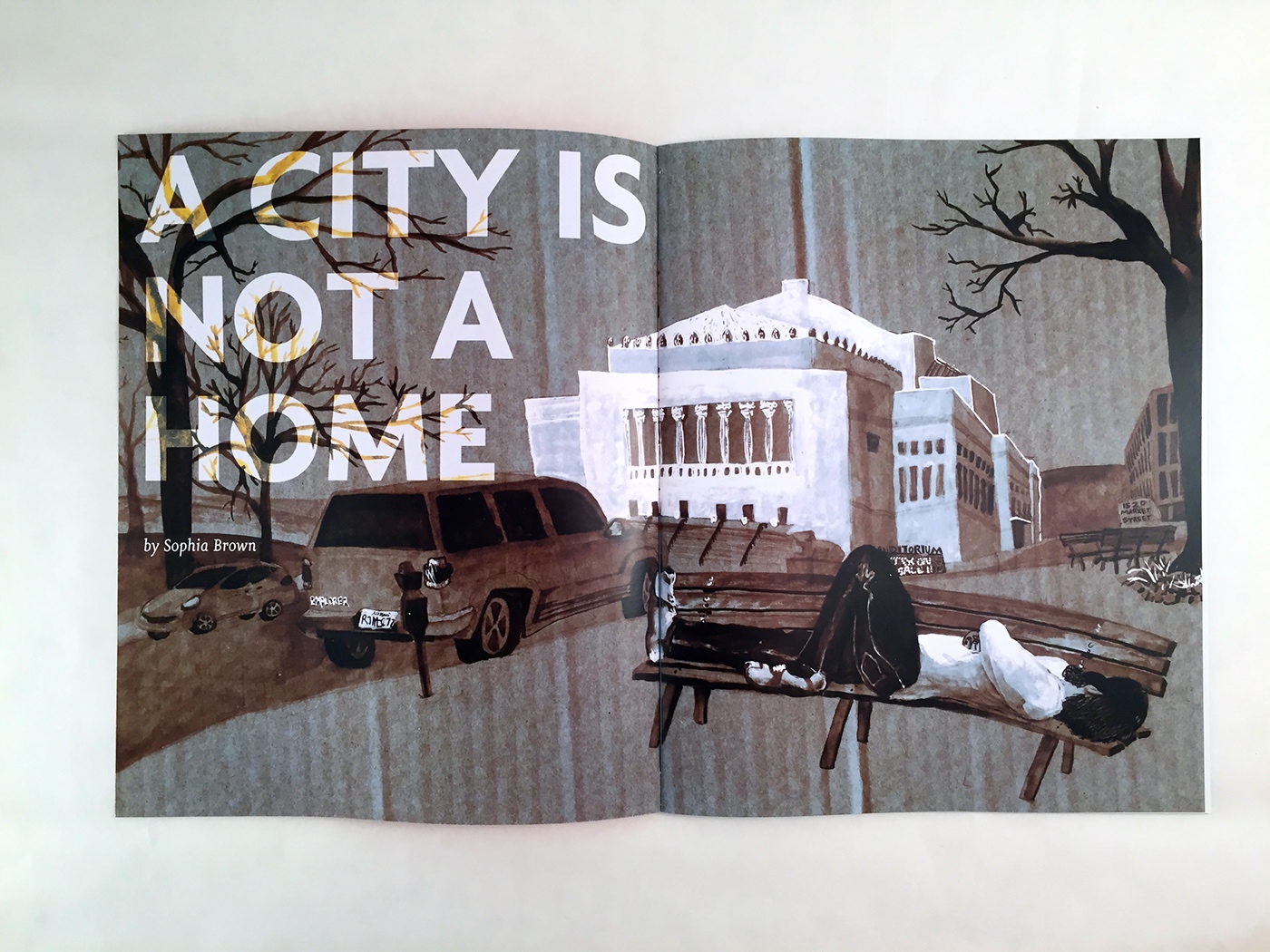

Before I go back to my home, I head to the park where Daniel says he spends time. It’s the one that runs several blocks along Market Street, and though I’ve been around here before, I never noticed how it lacks secluded or private places. It’s a very open plan right next to the Peabody Opera House, and I vaguely recall having sprinted through here to make it on time to The Book of Mormon musical. The arch peaks out from behind a building down the street. A man in a business suit crosses the park, passing a group of seven or eight homeless people hanging out on wooden benches. Neither party acknowledges the other. How does a community become so invisible in the heart of the most heroic area of the city?

A sign reads, “Park Curfew 10PM–6AM.” All parks have curfews, and a day ago, I might not have noticed this posting. But I’m suddenly and viscerally offended at this subtle, but sure-handed way to tell people like Daniel that even the most uncomfortable benches don’t have their back when the world goes to sleep.