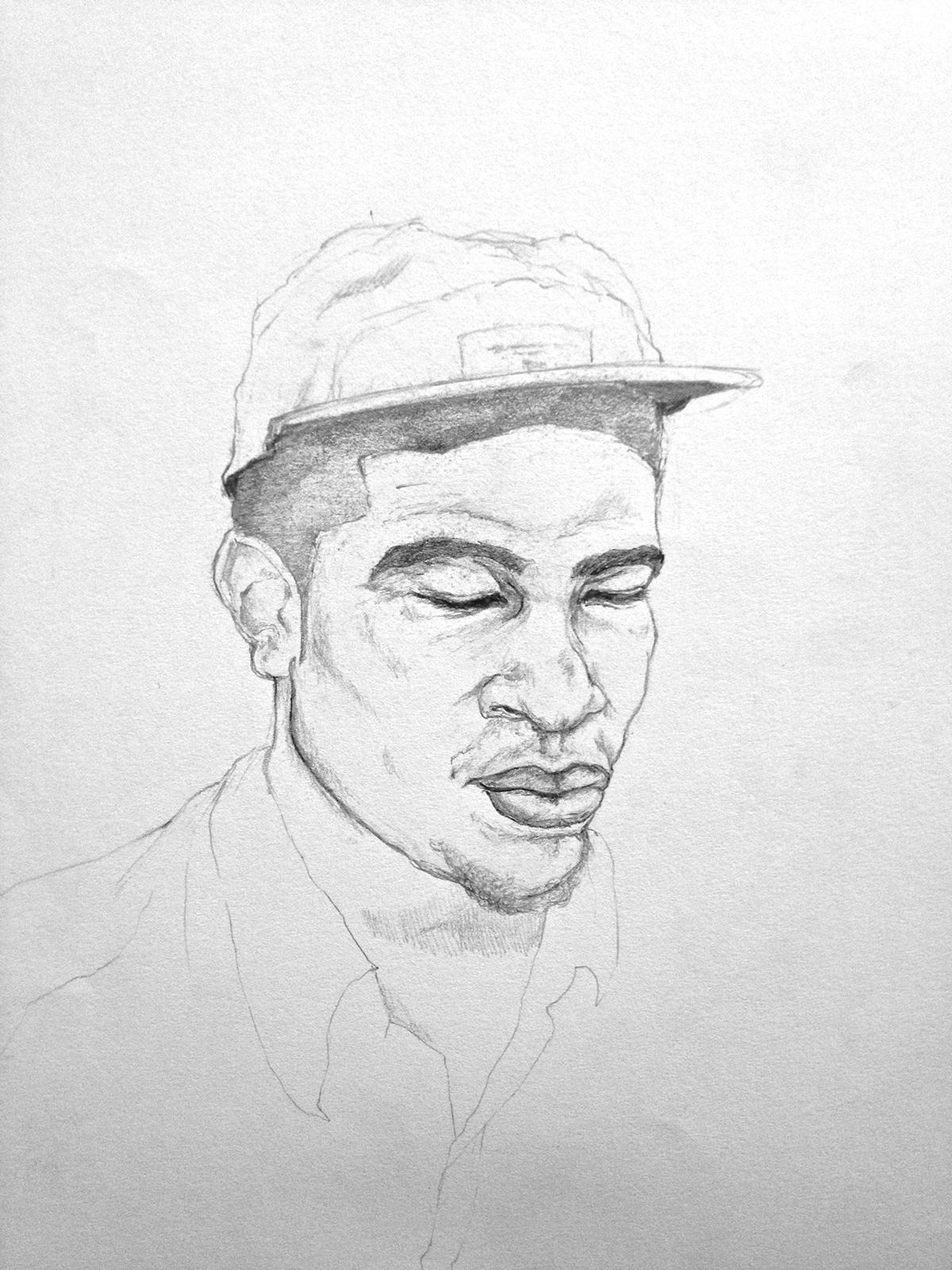

Jordan, from life

2013

Graphite on Paper

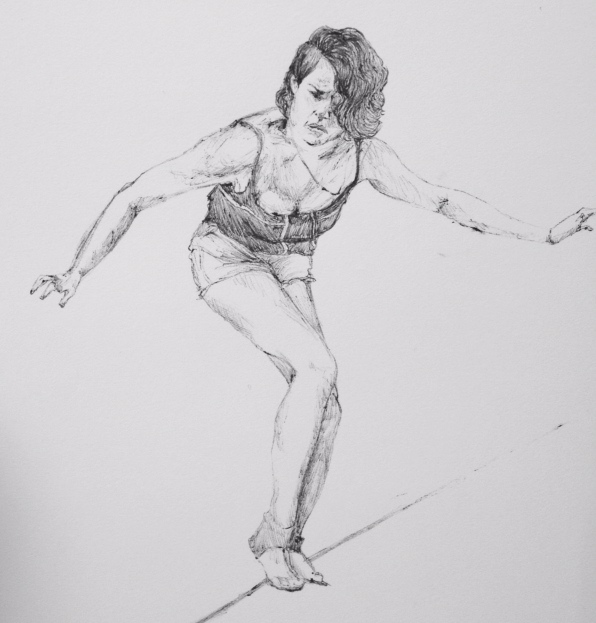

Caitlyn, from life

2013

Graphite on Paper

Seville

2013

Pen on Paper

Your Choices Are Not Your Own

2013

Pen on Paper

Your choices are not your own, they’re a timeline of your design which I tie too tight around my finger. Too tight, too tight, it turns purple and I watch it.

Never cut me free, I drink the tension.

You Cannibal You

2013

Pen on Paper

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Adopt a Survivor program pairs select Jewish teens with Holocaust survivors living in their area for an eight month long interview and research process. During that time, the students are offered a firsthand account of the horrors imparted on the Jews- and people of other minority cultures- during the second World War, and the last generation of survivors is given a voice with which to pass on its story. The project is as much a documentation opportunity as it is a relationship. The adopter spends weeks talking with his/her adoptee, revisiting his/her life, how it changed. Eventually the student writes a three page summary of his/her survivor’s biography, accompanied by a creative project celebrating the survivor. The program is emotional, opening locked doors for those trying to forget the torture and imprisonment in their childhoods, and altering the outlook of a generation of Jews on a piece of recent history.

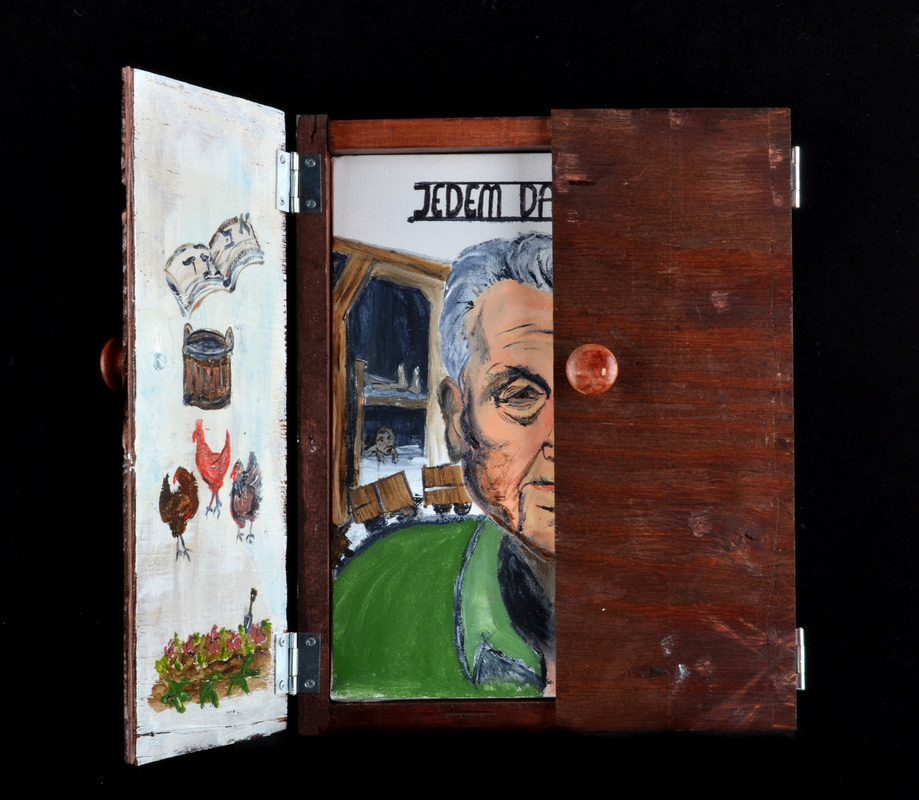

Attached is the work I did for and about Bernie Frydenburg, a Polish Jew, now living in Meriden, Connecticut. I was selected for the Adopt a Survivor Program during my Junior year of high school, when I completed the project, and continued to work with Bernie educating students throughout my senior year and into this Spring.

As a “thank you” present for my effort, Bernie built me a handmade jewlery box. The performance piece I created based on my thoughts and experiences with Adopt a Survivor employs the box as a representation of the man who built it, receiving the words of my poem.

Bernie Frydenberg was born on October 8, 1925 to Bluma and Moishe Frydenberg. They lived in the small town of Demblin, Poland with his two brothers and one sister. His father was a shoemaker who specialized in making boots for the Polish officers and had lost an eye in WWI, fighting in the cavalry. The family was fairly poor due to the recession, and his father had to trade shoes for coal and food. To make more money, Bernie’s older brother learned shoemaking as well, while he was in school. Bernie went to a Jewish school in which he learned the Hebrew alphabet, and how to read from the Chumash and Siddur. He was taught by a strict rabbi who would whip disobeying students with his belt. On one occasion, Bernie even stole his belt, and hid it in the ice outside the school. It was here that he learned Yiddish prayers with approximately thirty kids from the ages of six to eleven.

The town of Demblin was about 100 km from Warsaw near the Vistula River. A brook ran right past his house, and it was there that he spent his Saturday afternoons after coming home from temple. Bernie used his mother’s washing tub to swim in the brook and he charged his friends, who paid him in buttons, for rides in it. His mother also made money there by washing small wooden pickle barrels for the rabbi’s wife. Money was especially tight for the Jews of Demblin, as the government wouldn’t hire them and priests would tell their congregants not to buy from them. Even so, Bernie’s family upheld their Jewish lifestyle. The family went to synagogue every weekend and had Shabbat dinner. Bernie and his younger brother, Leo would take the chicken that laid the least eggs to the butcher to be slaughtered. He also planted beans, potatoes, and radishes in their small garden, and brought water from the well to cook with. Despite their poverty, his father would invite a poor man to spend Shabbat with the family. One time, his father, trying to be hospitable, said “Don’t be shy, have a piece of bread,” to which the poor man responded, “Yes, but the challah is worth all the money in the world.” Shabbat was a time they spent with their relatives. His father’s younger brother and his family lived nearby with his four children who they visited often.

This was before the war, when Jews were able to freely practice their religion. When the war broke, Bernie’s religious training was halted, and neither he nor his brother Leo were able to celebrate their Bar Mitzvahs. Anti- Semitism rose for Demblin was located near military interest: the railway station, the airfield, and a fort. Expecting bombs and chaos, many townspeople fled, only to be killed by German planes. Bernie’s mother decided to escape with her family at nighttime to avoid being seen. Each of the remaining family members took one chicken, which was later released because it was too heavy and they found an empty house to hide in. They continued farther and found a merchant who sold corn oil who would take them in for a week. When they ran out of places to stay, Bernie and his family returned to Demblin, greeted by the German army. They had arrived on three-wheeled motorcycles with two on a bike and no tanks but took charge of the town. None of the Polish residents opposed them. They even played a game where they made a Polish man dig a hole, then they would shoot him and bury him in it.

The Germans had brought a truck in which they would take men to work. One person from each family would report to the market for work everyday. This rule was established by a Jewish committee created by the Germans. Since Bernie’s older brother made the family’s income, and his little brother was too young to work, Bernie was sent to the market. He helped on the railway which was guarded by a soldier. Life in the ghetto was hard, and conditions left them unhealthy. The entire family contracted Typhus. Luckily, Bernie’s mother treated them by heating a glass with a candle and putting it on their backs. One day, in the spring of 1943; everyone was chased out of their homes to the marketplace. They were taken to the railway station and they began to board trains. Bernie’s brothers managed to run away safely, but his mother and sister were taken onto a train. He tried to join them, for he didn’t want to be separated from his mother, but she told him to run away to the village. Not wanting to disobey his mother, he crawled under the wagons into a corn field. He stayed there for a night, and the next night he found a customer of his brother’s who offered him safety for only one night. Again, he had nowhere to go, so he hid behind barns. He slept on piles of manure and hid in the straw. The next day, he ran out of provisions, so he went home to try to get more clothes. On his way, he spotted a group of Hitler Youth who were shooting whomever they saw, even if they weren’t Jewish. Therefore, he went back to the cornfield. A few weeks later, Bernie went back to the railway station and joined a group. The railway station now had a fence surrounding barracks, and each corner had a solider stationed on it. It was here that Bernie found his younger brother Leo, but he would never see his older brother again.

In the winter, Bernie was transferred to another camp on an airfield. He bribed a guard to put Leo on the list, and the two arrived at the camp along with some 3,000 people. Conditions were horrible, as a man could be hanged for as little as stealing a bar of German soap. To avoid this, Bernie discovered that he could clean his shirt by burying it in the snow. This was wise, as the camp was infested with bugs and lice. The camp was run by Viennese Jews and led by one man. His wife was interested in Leo, so he was transferred to work in the kitchen and he and Bernie were given more food.

After a while, Bernie and Leo were transferred to yet another camp. On this day, they were not taken to work, but rather marched to the train. They boarded with only enough room to stand and were given no food or water throughout the trip. The camp was in a religious Christian town with many factories. Here Bernie was stationed in a foundry, where they would melt steel to load onto wagons. On one occasion, the heavy metal fell and smashed his fingers. He went to the infirmary where sticks were tied to them, and he was told to keep working even with his injury. However, working with steel in these conditions could have led to far more serious problems. Other workers were producing a thin wire from the metal, about a quarter inch wide. Naturally, the wire was hot, and it was dispensed by wheels. The prisoners had to rub it with pincers, rolling it into coils. However, if the wire came out too fast, it could wrap around them, burning them to death.

From there Bernie and Leo were transferred to Buchenwald. This camp was large and he noticed there were gas chambers. As they stood outside, waiting to go to the barracks, the guards forced prisoners to undress, and jump into a large pool of disinfectant. Bernie heard the screams of those who jumped in before him, and he could see that they were in pain. Everyone left the pool with their eyes burning. If you hesitated, a guard would break your back with a block of wood. Bernie hadn’t yet been beaten by a soldier for misbehaving, so he jumped in. The disinfectant stung, and he was in pain for at least a week after the incident. Every morning, the guards would count the prisoners, and those who had died were collected in wheelbarrows. Those fortunate enough to survive would be sent to work. Bernie took a daily train to Weimar, near the camp, where he would clean up rubble from bombed houses. This job would discourage Jews from escaping. Since the former occupants of these homes had stored food in their attics, Bernie was occasionally able to steal some apples for him and Leo to eat.

A while later, Bernie and Leo, were taken to Colditz in 1945. There were prisoners from all over; places like France and England. Bernie worked in a factory in army ammunition factory. He was in charge of sweeping the floors. It was the spring of 1945, and at this point, though no one was aware of dates and times, it was obvious that the Germans were losing the war. Therefore, they wanted to kill the rest of the prisoners. The guards made the prisoners walk to Theresienstadt. This was the first time during the entire war that Bernie was separated from Leo.

The Death March was long and cold through the hills of Sudetenland all the way to Czechoslovakia. The prisoners weren’t aware of where they were going, and they had no coats to keep them warm. Most of them had wooden shoes, but they would stick to the snow, slowing them down. If you couldn’t walk, you were instantly shot, and pushed to the side of the road. Since the walk took three to four weeks, the prisoners slept in barns, or outdoors, without provisions. Bernie was lucky enough to have a blanket with him, which kept him from freezing to death. He was in constant fear that someone would rip it off of him in his sleep. While they were walking, an elderly German soldier asked Bernie to hold his rucksack for the remainder of the trip. He gladly accepted, knowing the guard would feed him extra in return. However, the bag became too heavy after a while, so he shared the load with an acquaintance, splitting the bread he was given. Because of this, they both survived. During the journey, some prisoners thought that the war had ended, so they took the rifles from the Germans but the uprising was put down.

After a short while in Theresienstadt on May 8, 1945, Bernie heard a commotion. He looked out the window to find Russian tanks liberating the camp. The gates were smashed, and everyone ran frantically looking for food. The Russians threw cans of pork lard, causing those who ate it to get sick and die. Bernie left the camp and started walking, when, miraculously, he found Leo! The two went to Liverpool, England where they lived in a hostel with other young survivors. The children formed a club called “the Primrose Club” where they would often play soccer and go on outings by boat. Here, they learned English, and continued to study Hebrew and Judaism. They moved to Manchester and then London, where Bernie learned to become a woodworker at age 19. In the spring of 1948, Bernie went to Marseilles to train for the Israeli army, serving for two years in the 72nd brigade. While Bernie was fighting the war of independence, Leo moved to Canada and became a welder and then a manufacturing agent. The next winter, Leo returned to London and asked Bernie to join him in Canada. Bernie agreed and they both moved to New Foundland selling factory samples to merchants. They had much business in Canada, as they lived in a prosperous area with fishing and woodcutting. There was a Jewish community with a synagogue. They store their goods in the spring, Leo would distribute in a van, while Bernie would sell from a boat. After six to seven years, Bernie went back to England and got back his job. A while later, Leo informed him he was to be married and Bernie returned to Canada. He stayed in a couple’s house with relatives in Meriden. One of these relatives had a niece Bernie’s age who she wished to fix up with him. So, one day, she invited him over to repair one of her front steps, as he had training as a woodworker. To his surprise, when he arrived, the step was not broken! That day he met the woman’s niece, Phyllis, and they got married in 1962. That November, he moved into her house in Connecticut, and they now have two sons named Alan and Mark, and three grandchildren: Rachel, Matthew, and Leah. Bernie finally had his Bar Mitzvah on June 6, 2010 joined by family and some survivors.

Bernie

2011

Acrylic, Canvas, Stained Wood

Bernie, detail

2011

Acrylic, Canvas, Stained Wood

Audio: “My name is Bernie Frydenburg and I was born in Poland. And...uh...and I’m a Holocaust survivor.”

Hey there

Hi

or maybe just shalom

its hard to choose a language

when you don’t have a home

Ive been here reminiscing

on someone elses life

and how its so weird that i get so scared about shit that’s never happened to me

But its a culture

its a look

and i hate saying that to you

you’re a man

not a book

and the words you share with me are true

And what if I forget

And what if no one knows

The beating and the killing, marching barefoot in the snow

A man on a soapbox six million feet tall

playing god with your family as puppets

But in ten years

or fifteen

all the horrors

that youve seen

They will lie in your grave

and theres no way i can save you

You, a man

To suffer years neath shadows cast

by chimney’s breath

and then at last

to die because your body wanes

You, a soldier

Die in vain

And to think about a young girl hearing stories all the time

Shit you say is in the past but is always on her mind

Put to death for being Jewish well then what the fuck am I

I guess she’s just a coward who is too afraid to die

I know people who hear stories like yours and they think its just a lie

Why

How can I

Be faithful to a history but not sound like a preacher

I’m a student and an artist not a social studies teacher

I need time

To be me

Before I can handle you

But you’re running out of time as well

What would you like me to do

I’m not mad that you sit there

And you’re looking like an object

I’m just sad that you can’t hear

and that this is just a project

*sips tea*

...oh

The Modern American Jew

2013

Oil on Canvas