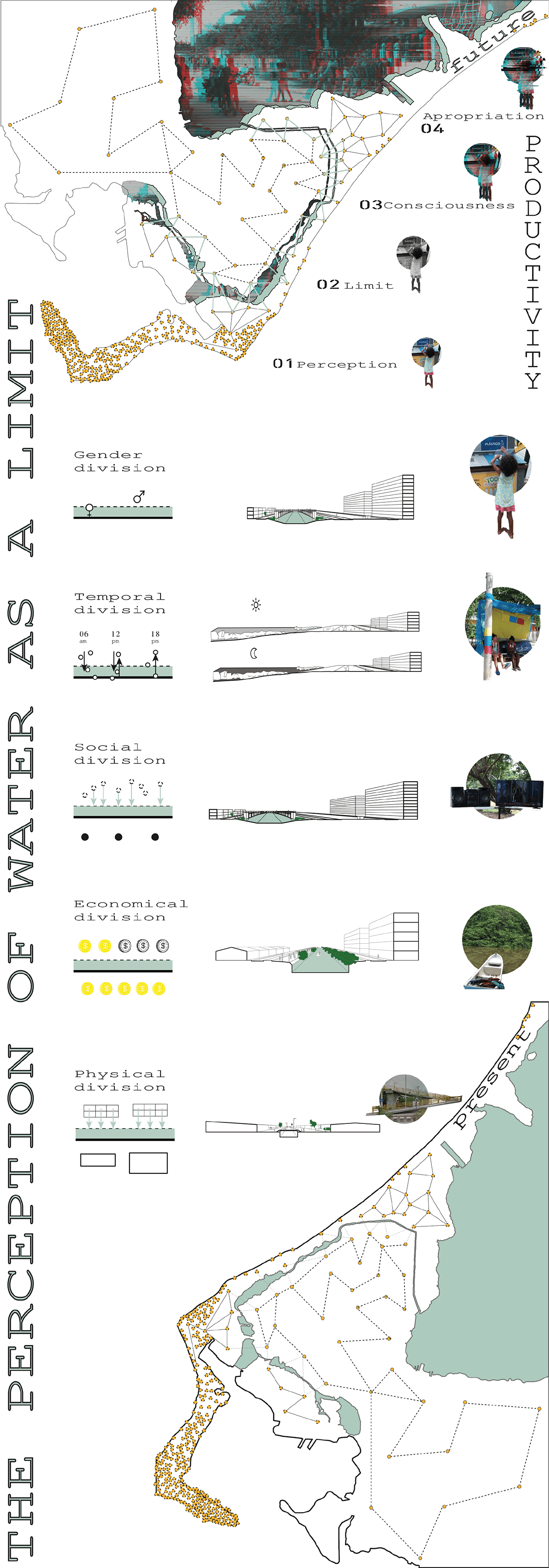

We were tasked to analyze a series of vulnerable communities in Cartagena, Colombia and their way of life. From the pool of communities, we were to choose one that caught our attention, and create a project that would create a more resilient way of life for them, especially as all of them were developed in a dangerous proximity to water bodies. As we walked along the Juan Angola river, we started noticing small actions that we couldn't account for, that didn't seem match our understanding of the relationship with water. These actions we called "glitches".

During the first part of our project, we understood a glitch as the sudden malfunction of the border as a limit, or, in other words, as an unexpected change in the meaning of the waterways for the community, as they develop into places for connection and social encounter. These glitches initiate processes of awareness-building and community appropriation, which shift the residents’ perceptions of the waterways as borders into essential shared urban spaces.

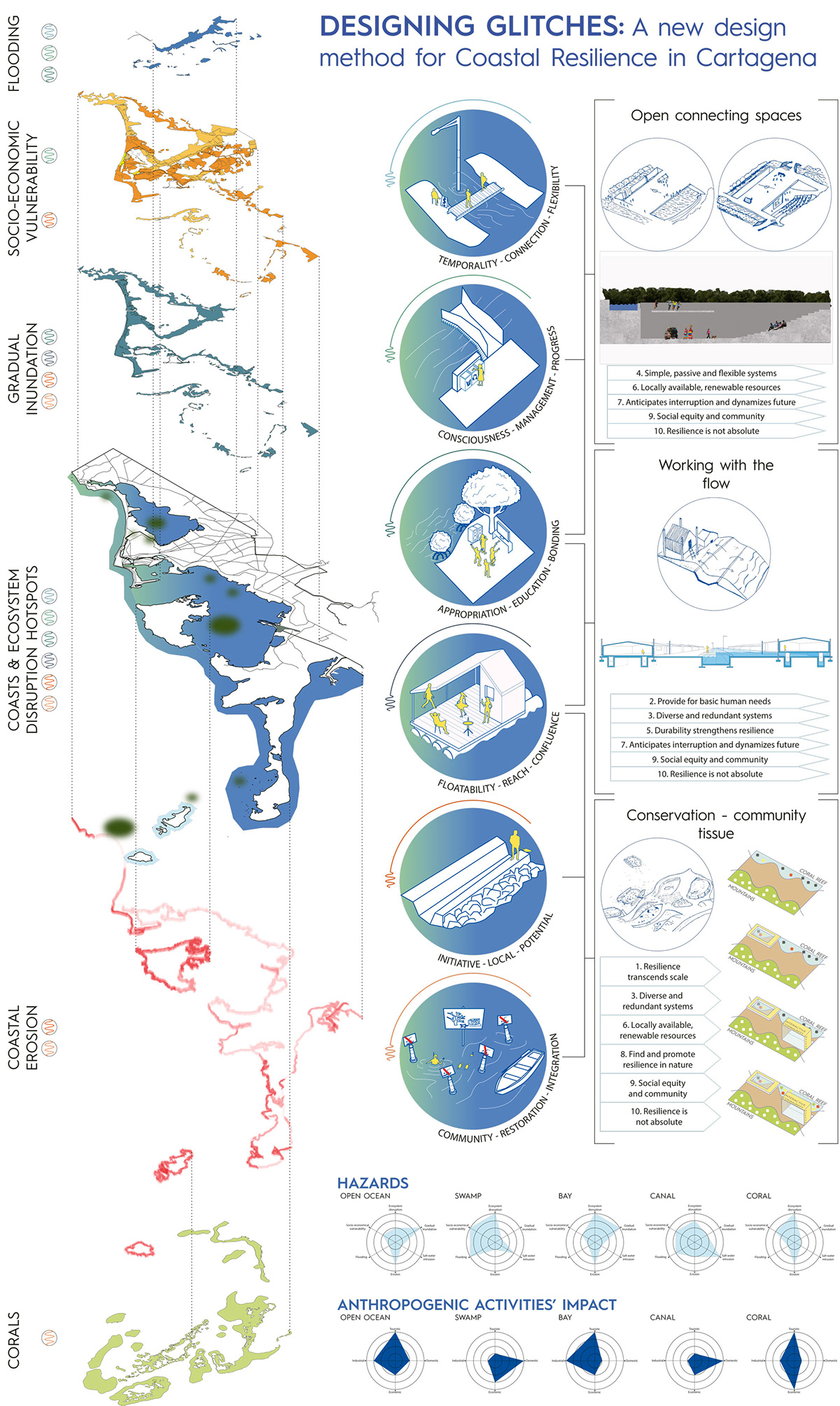

After developing the second phase of our project, we understood that glitches not only broke the perception of borders or limits between communities or between a waterway and a specific community, but we also saw how these glitches were an entry point that empowered people into being resilient and adapting to temporal or even new conditions that arise from different phenomena.

Nevertheless, and although the glitches we identified had the best of intentions, we stood on a critical position and recognized that these efforts were kind of shy. They were created in a most interesting way, but the impact they had was limited by their use or their design, which is why we strived to enhance what they can achieve, and empower communities by creating hotspots of resilience.

After developing the second phase of our project, we understood that glitches not only broke the perception of borders or limits between communities or between a waterway and a specific community, but we also saw how these glitches were an entry point that empowered people into being resilient and adapting to temporal or even new conditions that arise from different phenomena.

Nevertheless, and although the glitches we identified had the best of intentions, we stood on a critical position and recognized that these efforts were kind of shy. They were created in a most interesting way, but the impact they had was limited by their use or their design, which is why we strived to enhance what they can achieve, and empower communities by creating hotspots of resilience.

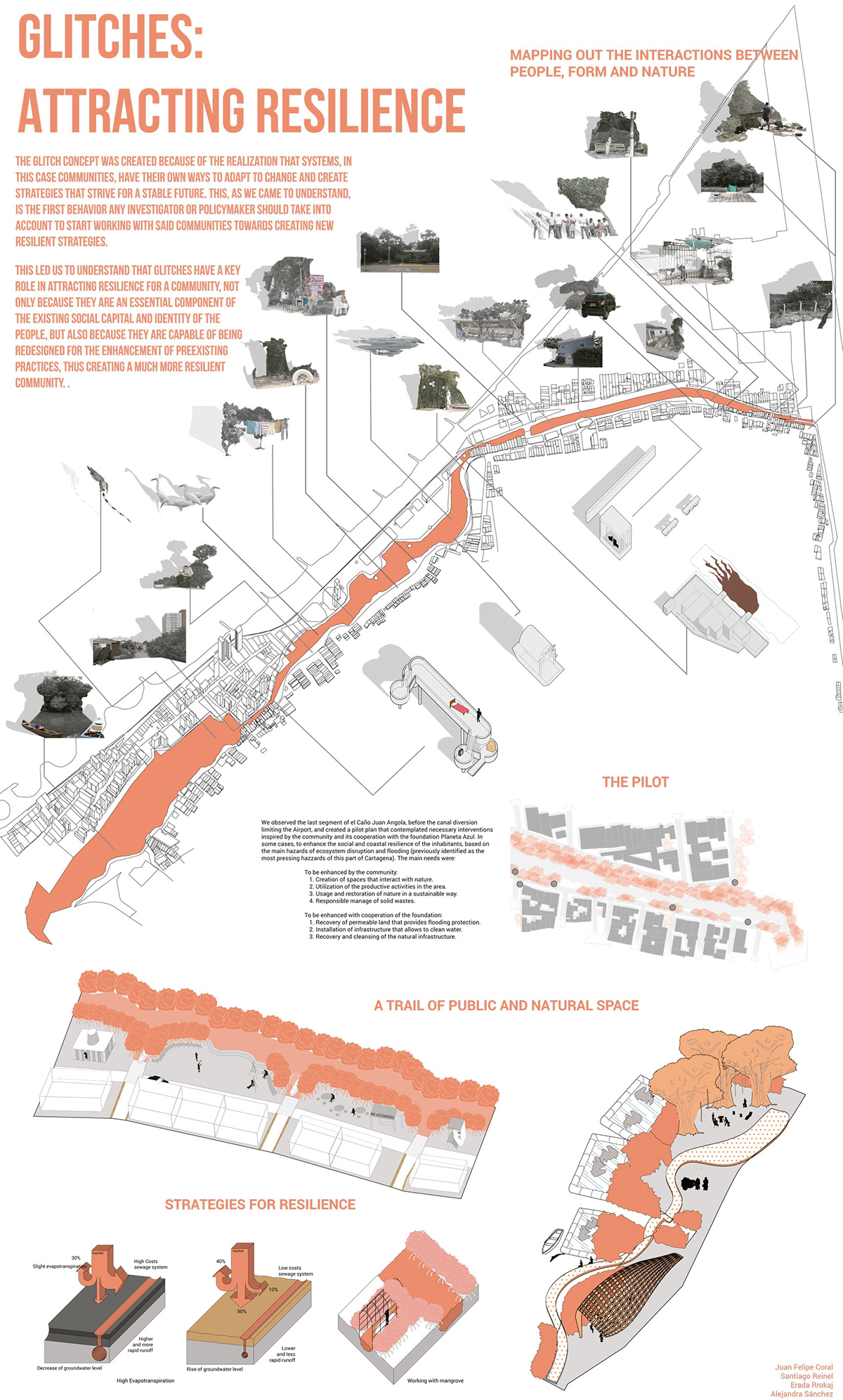

As architects and designers, we understood our approach to the community was limited by the time frame in which we had to create a project to enhance said resilience, and that an imposing, out of scale project would have been absolutely disrupting for a community that has developed resilient actions that are deeply connected with who they are, their collective way of life. However, we had the means and the knowledge to propose a series of small interventions that could maximize the impact, thus creating a more resilient community that still had control over their own way of interacting with water and their immediate surroundings.

What we came up with was a plan that could empower the community only with resources they had at hand, and that they could personalize as much as needed to achieve a resilient way of life. We identified 20 glitches along the Juan Angola river and we evaluated them using the 10 principles of resilient design, as well as categorized them to understand if they were disrupting social, environmental or economical aspects in the community. With that design approach, we started a pilot that reimagined each of the glitches in a more sustainable way, but one that could still be achieved only with the available resources as well as the knowledge of the local people and their trades.

This project led us to understand the importance of social capital to achieve resilience. As students and future architects, we are constantly creating projects that arise from our own understanding of a certain context, lot, problem or brief. However, we are rarely questioned about our understanding of the community or those who would be affected by the appearance of a new architectural piece: our word is final, and it's almost always backed by a structured analysis of the infrastructure of the chosen city or town. By eliminating the social factor, we are invalidating the most important piece of the puzzle: the user. If our target audience can't identify with a new project, or doesn't seem to understand the need for it, we failed at our job. As we came to understand, resilience is not achieved by large-scale projects or enormous interventions that seek to impose a certain conduct in a structured community: it arises from the curiosity and the tenacity of people, from the will to strive and to be better, even with the odds against them.

As we understood what resilience really meant, we came to understand our place in this equation: we, four aspiring architects that came from urban surroundings with no idea of how people in a vulnerable community in Cartagena lived day by day with the constant fear of being flooded by the proximity of a water body, became observers to try and learn as much as we could about the people we were designing for, without imposing our own, misguided, out-of-context point of view.

First delivery

Second delivery

Final delivery + catalog

Universidad de los Andes

Facultad de Arquitectura y Diseño

Departamento de Arquitectura

Proyecto U.I. Cartagena

Juan Felipe Coral, Santiago Reinel, Erada Rrokaj y María Alejandra Sánchez Rosas

2018, summer course